Not that long ago the most popular sports league in the country couldn’t run fast enough from days like Tuesday, when players began talking about police brutality and social justice.

Think about how much has changed in the last year. Think about the NFL’s reaction to Colin Kaepernick, even last winter.

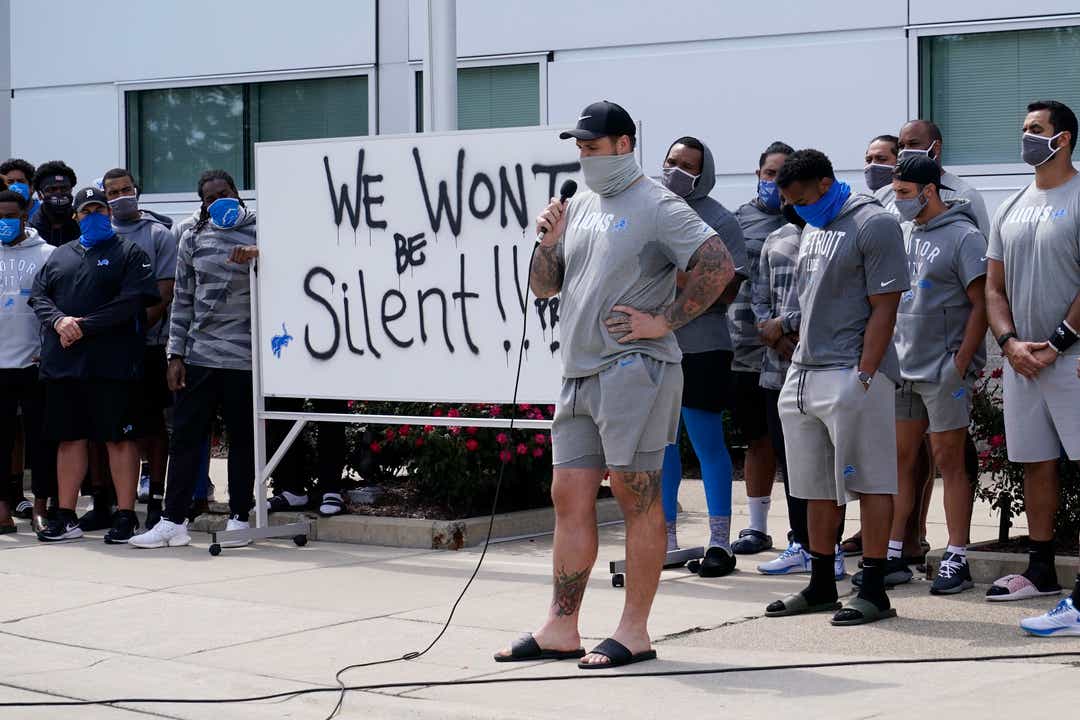

Then think about what unfolded in Allen Park Tuesday morning, when the Detroit Lions canceled practice, gathered to talk about the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, on Sunday, and quietly walked outside to the front of their headquarters in protest, carting a dry erase board offering these words:

“We won’t be silent.”

And:

“The world can’t go on.”

[ The Free Press has started a digital subscription model. Here’s how you can gain access to our most exclusive sports content. ]

No, it can’t. Not like this. And that’s the point.

So is this: Get used to sports and politics and society intertwining. No matter how much you wish it were otherwise. No matter how often you threaten to boycott the league. No matter how many times you counter with … ‘What about this or that?’

Well, it isn’t about that. It’s about a Black man who was shot in the back by police at least seven times.

Seven times.

And as long as these kinds of tragedies continue, sports will not be a distraction, but a reflection. On Tuesday, an entire NFL franchise halted its camp to hold up the mirror.

“We’re just trying to figure out what we can do to not only bring light to the situation of what happened and how it’s wrong with police brutality,” said Lions safety Duron Harmon, “but how can we as a team create change.”

You want to watch the Lions play this fall and forget about the pandemic for a few hours? Fine. You’re going to have to listen to what the team has to say first, whether you agree with the message or not.

No one gets to escape. Not now. Not with all this pain. Not with all the tumult as we sort through inequities of justice and try to level the imbalance in our history.

That we are here is both stunning and hopeful, and surely uncomfortable for many. Because for years, for decades, really, football games — along with so many other sports — have offered the best kind of respite from the difficulties of life. The game has soothed our weary souls. Offered us a chance to get lost in a burst of speed off the edge or a one-handed catch on the sideline or the thrill of a fourth-quarter comeback.

Sports, and football in particular, remind us what it looks like when so many zero in on the same moment, when we sync up and push through the impossible. It offers brawn and ballet, fast-twitch explosiveness and subtle misdirection.

It combines planning and improvisation and all-night film study. And it’s ours. All ours.

No wonder we crave its return. With a little luck, we’ll get it back in less than a month. We’re just not getting it back in the way we used to experience it.

The least we can do is accept that so many of the players in the NFL have grown up with a different perspective on policing, accept that these otherworldly athletes got to your Sunday television screen by surviving tense and demeaning interactions with cops, and that when they see video of a Black man getting shot in the back, it acts as a kind of trigger, releasing something similar to post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Those are the kind of stories that were shared Tuesday inside Lions headquarters. Like this one, passed along by offensive lineman Taylor Decker, who said a teammate’s mother demands to know when her son gets home from work every day.

It’s a 23-minute drive. Twenty-three minutes of anxiety for the mom.

Because her son has an out-of-state license and a different ID and to her those innocuous-sounding things to so many of us are reasons to fret for her son if he gets pulled over.

Hearing that stunned Decker. Knocked him in the gut.

“I have an out-of-state ID,” he said. “I’ve got a Michigan license plate. I’ve got a headlight out, and not for one second was I concerned about making it home for my safety.”

So, yeah, the world can’t go on. Not like this. Not when a 6-foot-7, 320-pound white man can drive home without a care in the world while his Black teammate’s commute ends with a message to his mom to rest her fears.

And so, the Lions stopped everything Tuesday morning. Stopped and talked and listened and walked in solidarity to let the world know they have a platform, that they intend to keep using it, that they have things to say.

“When people you care about go through things like that, it’s tough,” said Matthew Stafford. “And I wish America, I wish everybody could be on these calls or be in these meetings. I feel so lucky and privileged to be a part of it.”

We are a part of it. One way or another.

After Sunday in Wisconsin and Tuesday in Allen Park, that should be clearer than ever: our entertainment will no longer arrive in a vacuum.

Contact Shawn Windsor: 313-222-6487 or swindsor@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @shawnwindsor.